In an alternate reality (where I have more money and time), I’d love to study more neuroscience. For sure, it hurts my brain learning about the brain, but it’s such an amazing piece of hardware. Fortunately, Edward Bullmore’s book – The Inflamed Mind (2018) – gives me just enough of a platform to understand the current thinking and limitations when it comes to determining a physical piece of evidence for depression.

I highly recommend this book and there’s far too much for me to fully express how intriguing it is. Hopefully some of the key thoughts below will help you recognise that depression is not all on us. Depression isn’t something we can just will ourselves out of. We didn’t end up here because we’re weak. It’s more likely that we put the needs of others over our own, and need to give ourselves a chance to meet our own needs and to recover.

Edward Bullmore, a British neuroscientist, does a great job of laying out piece by piece the various factors that influence our treatment for depression, including the pervading Cartesian philosophy that the mental and physical are separate and how that impacts medical practice, as well as the restrictive cost of clinical trials for alternative drugs.

Treatment is separate for mind and for body

It makes sense to us that we might be depressed if we are physically hurt – say a back problem. But what if the depression is a symptom of the same source that is causing us to be vulnerable to back pain? The old 20th century thinking was that the immune response was separate to our nervous system due to the blood-brain barrier – that when we fight off bacteria and become inflamed as part of the immune response, and that this doesn’t cross over to our brain. But now we see signs that messaging does go across. The brain knows when our body is inflamed, it knows when our body is trying to fight off something.

Unfortunately change takes a long while to happen and it seems that when depression presents itself alongside a physical issue, a doctor will likely dismiss it as outside of their remit, outside of their domain of the physical body. It’s also easy for them to dismiss it as being obvious – you’d be sad if you had chronic back pain for months wouldn’t you? Conversely, a psychiatrist with the same mind-body division, might dismiss any physical source of a mental issue – it must always be in the mind. The back pain is psychosomatic, made up as you’re too anxious to go outside, rather than because of an actual injury.

When clients say to me that they are anxious, I try to get them to unpick the different elements that signal depression – are there any particular thoughts, any physical sensations, and what order do they come in?

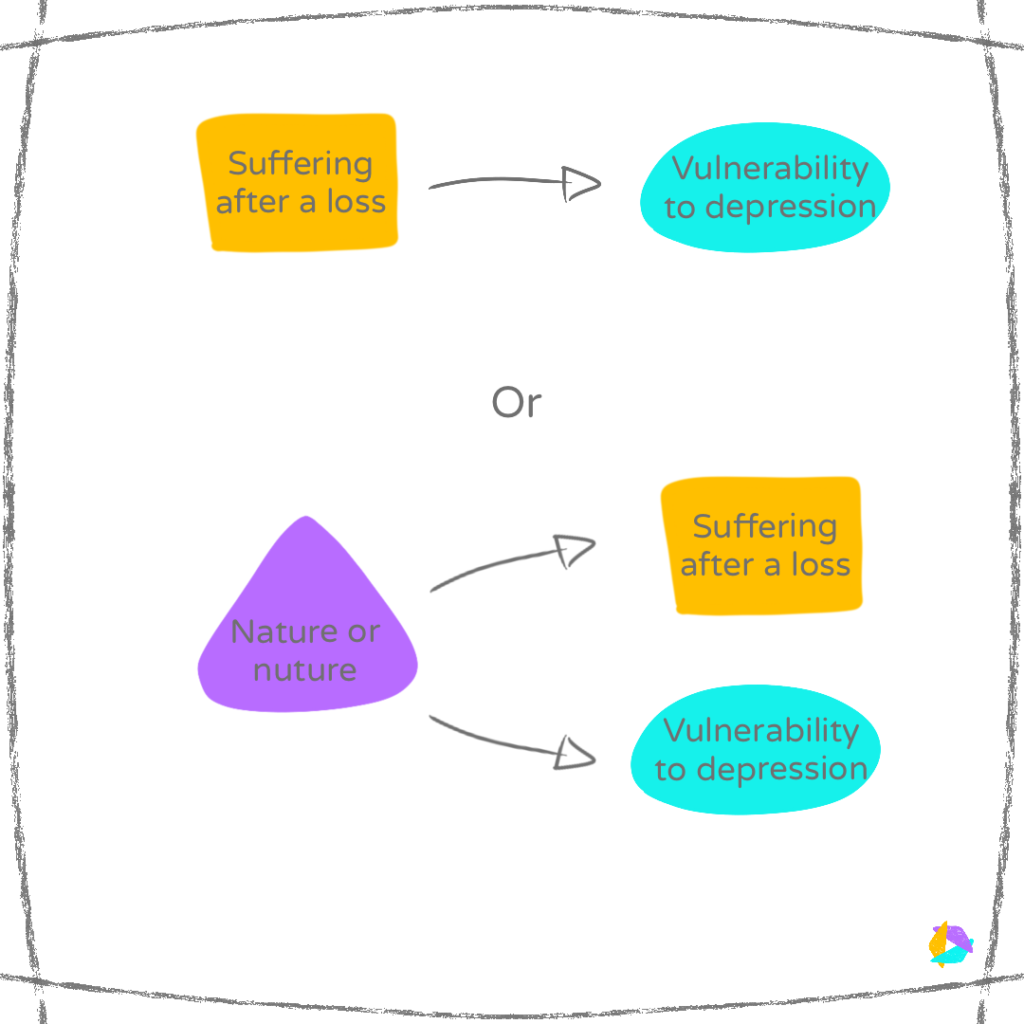

Yes, you could be depressed because you suffered a great loss this year.

But yes, you could also be depressed because you’ve not slept well for months, and that may or may not be related to the loss.

For me, this is where our own judgement needs to hang way back and we need to return to basics. Are we sleeping well, eating well, getting out and moving? If those aren’t in place, we are more vulnerable to thinking that we are weak and failing at managing…well everything.

Drugs can be valuable but treatment methods are slow to change

When we’re struggling, obviously we want to feel better quickly. For some, anti-depressants give them that extra headspace, taking the edge off extreme lows. I refrain from using the word “boost”, because the fact is, we don’t really know why they work. One idea is that it boosts the levels of serotonin, but there is no evidence that serotonin is unbalanced in a person with depression. Furthermore, because of this mind-body divide in medicine, there is no physical test like a blood test or any biomarker in psychiatry. Depression is diagnosed by a series of observations, a correlation, and not by causality. Part of the issue is that it is difficult to accurately assess the levels of serotonin in the brain – the relevant areas are too small to scan, levels in the blood are not representative of levels in the brain, and tapping into brain levels via a lumbar puncture is far too invasive.

Even though depression will be the single largest cause of disability worldwide by 2040, there have been no breakthrough advances in the last 30 years, i.e. since Prozac was launched. Clinical trials are costly – in 2010, getting a drug to market cost on average $850 million. So the shortcut method is to find drugs that give the same side-effect profile as old anti-depressants, rather than discover new targets. This reverse-engineering makes assumptions on how the drugs are helping. Furthermore, there isn’t enough recognition that certains drugs might actually perform better for specific types of depression over others and that the drug efficacy is being lost by combining all the data.

Fortunately, there is more of a recognition that one source of depression may be related to inflammation in the body. Such inflammation can trigger inflammation in the brain, and cause the changes in thinking and behaviour that we see as depression. Other than waiting for drugs that target inflammation, we can reduce the expression of inflammatory genes in our bodies by mind-body activities such as meditation, mindfulness, yoga (“Mind-body therapies and control of inflammatory biology: A descriptive review”, Bower & Irwin, 2016). My thinking is that such activities give our bodies the feedback that all is well, we don’t need to be alert, we don’t need to be in fight/flight mode. Depression kicks in when we don’t give ourselves enough recovery time. The immune response kicks in to fight off an infection and there isn’t an off switch. Our bodies protect us by keeping a record of antibodies, such as the vaccinations we got as a kid to fight off infections. What if similar immune responses protect us from actual or potentially difficult life events?

Depression as a form of survival

What is the value of being depressed to ourselves and society? Could it be a lag in evolution? 150,000 years ago back on the savannah, what starts as a small infection could be fatal so our body works hard to get rid of it.

If we are fighting of an infection, we need to isolate:

- To help us conserve energy and recover

- To not pass anything to anyone else

But we’re also vulnerable on our own, so we need to be alert to any danger – hence restless sleep.

Whether it be an infection, a major life event or chronic stresses, perhaps depression is our body’s way of just trying to keep us physically alive, to rest and recover. We could be vulnerable to depression as a result of the makeup of our immune system and/or the habits we learnt growing up. Sometimes we do ourselves a disservice when we don’t recognise the range of possible factors at play.